Governance determines who has the power, who makes the decisions, how other players make their voice heard and how account is rendered”.

A year ago I adopted this definition of governance from the Canadian Institute on Governance as it’s the most elegant one I have come across. I decided it was necessary to add it to my collection of mantras after we held a seminar for those governing in multi academy trusts (MATs) and many delegates agreed with a suggestion from an executive leader that we shouldn’t talk about power. But he was missing the point, as do many other executive leaders and educational commentators who are not familiar with governance literature.

In recent years the Secretary of State has acquired additional legal powers, usually at the expense of local authorities, but I wonder if Department for Education has really realised the extent to which it has handed over power in the schools system to governing boards. The reach of that power for individual boards becomes more and more significant as trusts grow and become responsible for the education of more and more pupils (there are at least six MATs with over 20,000 pupils each), but the principle still applies to the governing bodies overseeing tiny schools.

Lord Nash, the governance minister for the past four years, says in his foreword to the DfE’s 2017 Governance Handbook published in January: “Governing boards have a significant degree of autonomy in our increasingly school-led system. They are the vision setters and strategic decision makers for their schools”.

NGA has been spending much time over the past four years helping those leading schools understand that a vision is not just a few alliterative adjectives, but a description of where the school and its pupils are aiming to be in a few years’ time. A rhetorical genius (Martin Luther King springs to mind) can get away with “I’ve got a dream” which inspires others to take action, but the rest of us mere mortals have to come up with a strategy which helps realise that vision. This year we are planning to update and improve the guide on strategic planning we produced with the Wellcome Trust in 2015, and add a section on the governing board’s responsibility on ensuring a healthy culture. But the freedom to set a vision only makes a difference if we all had the confidence to do what we think is right, rather than continuing to look for hints from on high.

Anyway, if we can’t rid ourselves of the propensity to look upwards for inspiration, where is the vision for the school system as a whole? Michael Gove’s “let’s have a thousand flowers bloom” and lots of stand-alone academies was shown to be flawed within a couple of years. While there were a few true believers in the total autonomy vision, many just paid lip service. When NGA made the case for federations, groups of community schools collaborating under one governing body to improve the offer to pupils, we were considered at best rather quaint and behind the curve but at worse subversive, beyond the pale, not worth talking to! But how times have changed: now groups of schools are the order to the day and NGA led the understanding of MAT governance as Lord Nash commented to the Education Select Committee in November.

We of course welcome this change to embrace collaboration, but it has left the vision from on-high a bit blurred. Growth of MATs has been the order of the day from the DfE for the last couple of years, but their preferred end point is unclear. Lord Nash thinks there could be tipping point in five or six years. Some school leaders seem to hanging onto every word uttered by a Regional Schools Commissioner (RSC) in an attempt to see what might be expected. Many think financial constraints will make it inevitable that schools will join MATs to take advantage of economies of scale. If finances are expected to be the prime driver, the DfE is missing a trick with the national funding formula - there is no incentive built in there. What’s more, given a MAT board’s responsibility to balance the books, some schools will not look appealing as partners. Neither the Secretary of State, nor the RSC can insist a governing body of a good school converts or that a trust takes on more schools.

However RSCs do sometimes say no to particular schools coming together as MATs, and although the quality of those decisions may be improving, some are still difficult to understand. Why oh why in some places have we got so many empty MATs (single schools waiting for a partner)? Clearly no-one there was considering the vision for the area as a whole then, but reacting to individual applications. This is very difficult stuff, and in the absence of a strategic planning authority, was not going to be simple to resolve. So will the muddle be tackled, how and by whom?

Establishing trusting relationships is at the heart of this, and sometimes the values and ethos of schools won’t fit well together. Some others do not have the option of joining a group with their nearest neighbours; for example, the diocese plays a huge part in the possibilities for Church of England and Roman Catholic schools.

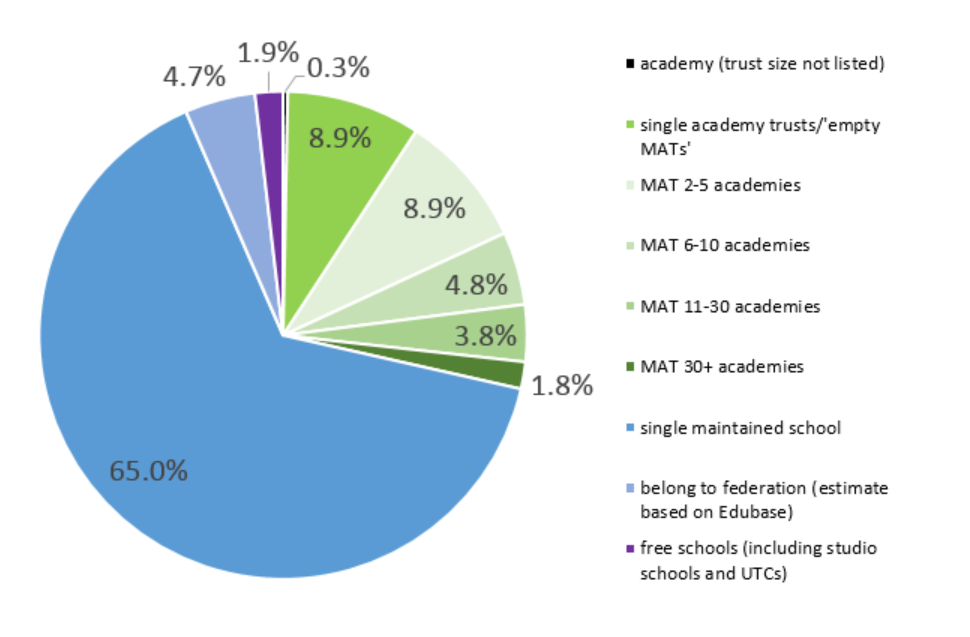

This graph reminds us where we are at present: despite the rapid growth in small MATs, almost three-quarters of schools remain stand-alone:

On all sorts of conference platforms, many of the edu-commentariat step into this muddle to second guess the DfE, often sounding as though they have access to privileged information. I don’t think they do. I have heard speculation ranging from six huge MATs across the country to many thousands. And though I probably qualify as one of those commentators, I am not mystic Meg. I know who will be making these decisions and, even though NGA probably has a better idea of the mood of governors and trustees across the county than others, I am not going to second guess those governing. I imagine it may be different in different places.

With the exception of underperforming schools, it will be governing boards up and down the country who decide whether or not they want to join a group and then how big they want to grow the group of schools. Trustees have a legal obligation to ensure that their trusts are sustainable and solvent, a going concern.

They need to weigh up the evidence in the interests of the pupils they are educating now and in the future. One slight flaw in that plan is there is a need for the better evidence; this was reinforced by the House of Commons Education Committee recently who recommended more guidance and research. Geography and ethos are important when forming or joining a group of schools, but there is unlikely to be a best size.

The select committee also pointed out that there has been too much of a rush to growth, and the best trusts had expanded cautiously. This is music to NGA’s ears.

So have governing boards become the real architects of the school system? When considering whether to join, form a group or take on another school, can and will schools and trusts have one eye on the bigger picture, the needs of the wider community? Is this always compatible with their legal responsibilities?

Even if this tension can be squared, how many groups of schools would one want in an area? How important is choice? In some areas, particularly for secondaries in small towns, choice is not even a practical suggestion, without lots of time for pupils and cost of travelling. Anyway, almost all research shows parents value a good local school more highly than choice. Do we really want a system with an ever reducing number of MATs and the increasing risks that builds into the sector? I would say not, but it is for governing boards to decide.

Our experience tells us that it helps if there is someone to hold the ring in discussions between schools or trusts. It is no accident that the areas with most federations are those where local authorities saw the benefits and promoted groups of schools, always between schools within easy reach of one another. This model was not initially adopted by the academy sector, but some have learnt the hard way. Gove’s vision was for a system without strategic planning, but might we need to move some way back towards that and if so, who will facilitate those local discussions? If other players do not come forward, RSCs may still find that they have a role to play in facilitating the creation of local visions. But will schools and trusts accept them as honest brokers?

Governing boards have been given significant freedom and responsibility to shape the schools system but do not yet appreciate their power. On the other side of the coin, has the penny dropped that the Secretary of State may no longer have the means to deliver the Government’s vision for school education? Those who wish to see the diminution of politicians’ influence on education should be rejoicing. And those governing need to grasp the opportunity to create success out of muddle in the interest of pupils.

Former Chief Executive

After 14 years with NGA, Emma has departed from her role as Chief Executive. During her tenure, Emma was a strong advocate for the school governance community, engaging with legislators, policymakers, education sector organisations, and the media on a national level.